By Max Nesterak

Ericka Helling is used to being attacked on the job. She’s been bitten, slapped, kicked.

“And that’s just a part of the day,” said Helling, a 27-year veteran nurse in the intensive care unit at M Health Fairview’s Southdale Hospital.

She considers herself lucky. Her coworker was punched in the face just a few weeks ago. More than one nurse she knows has had a traumatic brain injury from a workplace assault.

Often the violence comes from patients who are inebriated, delirious or in the midst of some other mental health crisis. Sometimes, it’s the patient’s family members. Last month, Helling’s hospital went on lockdown after a man visiting his mother pulled out a gun and struck his sister several times, according to court filings.

“We’re always concerned about what’s next, what’s coming, head on a swivel,” Helling said. “It’s not unique. Violence happens in every single hospital across this country.”

Health care workers are five times more likely to be seriously injured from an assault on the job than the U.S. workforce as a whole, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nearly three-fourths of all nonfatal workplace violence is against health care workers.

The antidote, according to nurses, is more staffing. More eyes to spot problems before they escalate into violence, and more hands to respond when they do.

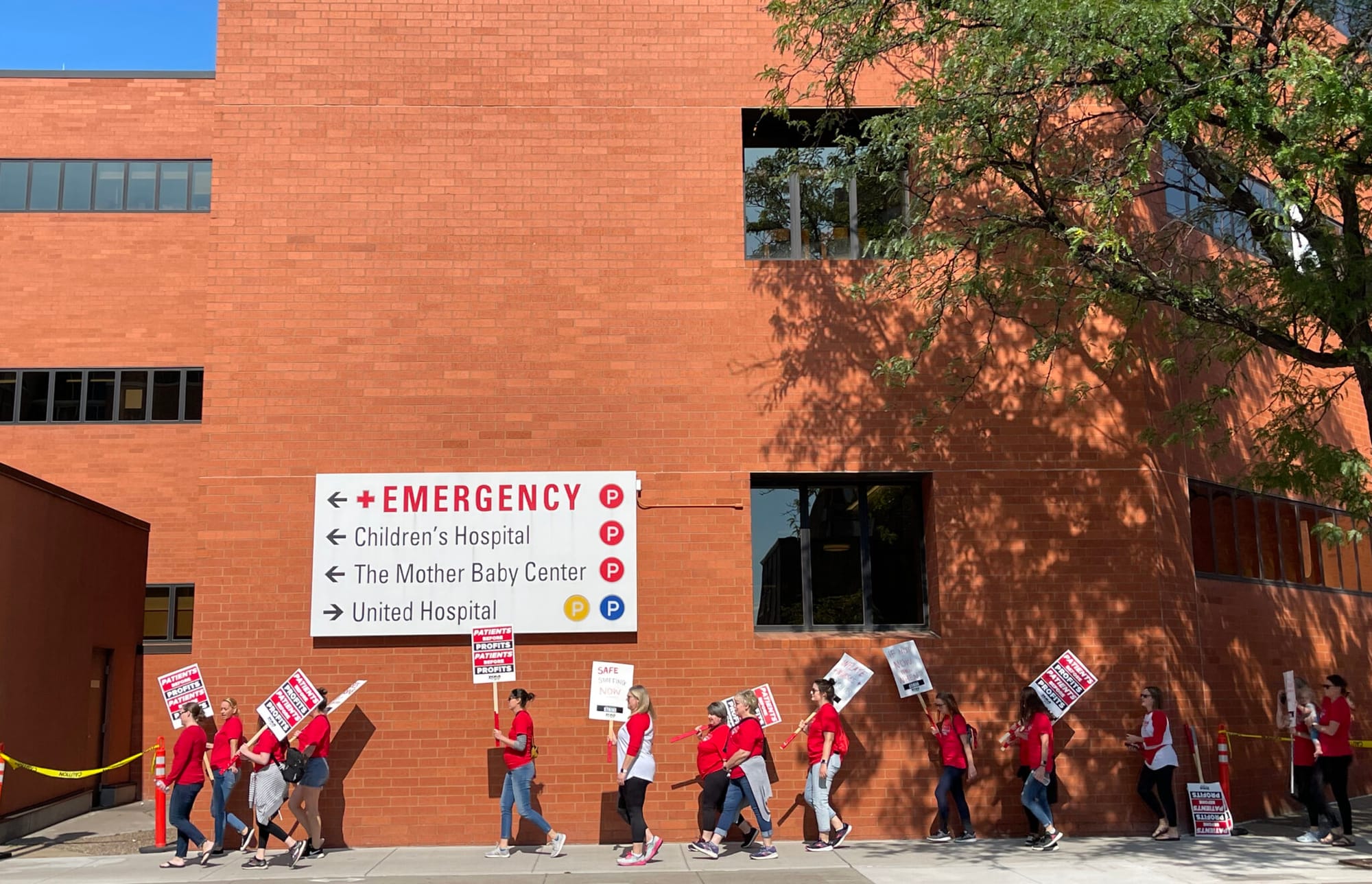

Union nurses with the Minnesota Nurses Association are intent on pressuring hospitals to commit to higher staffing levels as they negotiate labor contracts covering roughly 15,000 nurses at seven of the state’s largest hospital systems in the Twin Cities and Duluth areas: Allina, Children’s Minnesota, HealthPartners, M Health Fairview, North Memorial, Essentia and St. Luke’s.

The issue is so important to them, the union says, that nurses have ranked safe staffing above pay for the first time in their survey of members.

The union is becoming increasingly impatient and disillusioned with hospital leaders and the collaborative approaches like advisory committees they’ve won in past negotiations.

The contracts expire in May and June – and union president Chris Rubesch said a strike is on the table.

“We’ve been steamrolled. We’ve been ignored. So enough is enough,” Rubesch said, at a news conference earlier this month.

Ultimately they want strict nurse-to-patient staffing ratios to mandate a minimum number of nurses, which they argue will protect nurses as well as patients, who are facing rising rates of adverse events.

But staffing ratios have been a nonstarter for hospital leaders in negotiations. Hospital leaders argue staffing levels must remain a management decision because it allows them to respond to hour-to-hour changes in staffing needs. They say having to meet strict nurse staffing ratios would drive up the cost of care and force them to sideline lower paid workers like nursing assistants in order to meet quotas for registered nurses.

Looming over current negotiations are potential drastic federal funding cuts to Medicaid, which threaten to strain hospital finances, which leaders say are only just recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rubesch, the union president and a cardiac nurse at Essentia in Duluth, said his employer proposed stripping language from their contract that says staffing decisions cannot be based solely on budget concerns.

“Ask yourself why they are striking that language, if only so that they can staff to the budget and not to the patient’s needs,” Rubesch said.

Hospital leaders note that they’ve been able to hire many more nurses since the COVID-19 pandemic led to a wave of departures from the health care industry.

“Contrary to claims of a widespread nursing shortage and declining interest in hospital-based careers, the data tells a different story. Hospitals across the Twin Cities are seeing strong momentum in nursing workforce stabilization, with double-digit declines in RN vacancy rates over the past year,” wrote Paul Omodt, a spokesman for the hospitals in negotiations, in an email.

Nurse vacancies more than quadrupled during the COVID-19 pandemic — from 3% in 2020 to over 14% in 2022 — as burnout drove health care workers out of the industry. The vacancy rate is now down to 11%, according to the latest workforce survey by the Minnesota Hospital Association of most hospitals in the state.

The hospital association noted that just 2 in 5 registered nurses are working full time, a record low, which suggests the workforce shortage could be eased if nurses picked up more hours.

Nurses counter that the exhausting shifts with managers scheduling too few nurses on duty make a full-time schedule unsustainable. Plus, nurses say hospitals prefer to hire them part-time because managers can cancel their shifts when they believe the hospital is overstaffed without having to pay their wages.

“Hospitals aren’t hiring people at full time … because they want control over their staffing,” Helling said.

A recent search of open jobs for bedside registered nurses at M Health Fairview hospitals showed less than a third were for 0.8 full-time equivalent or greater. At Children’s Minnesota, only about a quarter were full time. At HealthPartners, just 1 in 5 open hospital nursing positions were full-time.

For over 30 years at the bargaining table and the state Capitol, the nurses union has been fighting for a greater say in hospital staffing levels. Over that time, staffing has only gotten worse, nurses say.

Three years ago, 15,000 nurses walked off the job for three days at 15 hospitals in what was then the largest private-sector nurses strike in U.S. history. The union won the highest pay increases in two decades – about 18% over three years — but negotiated only modest concessions from hospital leaders on staffing.

Minnesota nurses are the highest paid in the country after accounting for cost of living, earning about $94,830 per year on average. The union boasts that’s in large part their doing, and say those higher wages help attract and retain nurses who provide nation-leading care.

After the 2022 strike, the nurses union turned to the state Legislature and got as close as they’ve ever been to staffing ratios. In 2023, the DFL-controlled House and Senate passed a bill that would have required hospitals to create committees made up of nurses and management to set staffing levels. The bill was gutted in the final hours of the legislative session, however, after Mayo Clinic threatened to move billions in future investments out of state if it became law.

What was left of the bill included requirements that hospitals create procedures for health care workers to request additional staffing if they’re worried about safety, and to document those requests and submit them to the Department of Health along with written action plans on workplace violence. Beginning Jan. 1, 2026, the Department of Health must also publish an annual report on the state’s hospital nursing workforce.

Nurses struck out on staffing levels again at the Legislature again this year, having pushed for their ideal, no compromises proposal that would have set rigid nurse-to-patient ratios.

After their legislative defeat in 2023, nurses elected a new set of leaders that promised a more confrontational stance toward management and a strategy focused on organizing and public pressure campaigns rather than dueling with employers over grievances through legal briefs.

The current negotiations with 13 hospitals is the first major contract fight for the new leadership, who would seem to be at least as willing as their predecessors to lead their members to the picket line if they fail to win any concessions on staffing at the bargaining table. They’re also asking for increased security protections and more paid time off if they’re injured on the job.

Nurses opened negotiations seeking 18% pay raises over three years, while the hospitals started with 6%.

The nurses’ focus on staffing to improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of violence is backed up by research.

Patient deaths and hospital readmissions were also found to be higher when fewer nurses were on duty, according to a study of New York hospitals by researches at the University of Pennsylvania. The researchers estimated that more than 4,000 lives and $720 million could have been saved over the two-year study period if hospitals were staffed with 1 nurse per 4 patients rather than the average of 1 to 6.

A study of Illinois hospitals similarly found patient deaths and hospital stays increased as nurses were given more patients to care for.

As for violence, OSHA lists understaffing, high turnover and long wait times as risk factors for violence, all of which are plaguing Minnesota hospitals, nurses say. OSHA also says working alone and in isolated areas contribute to the potential for violence.

“We deserve the right to go to work and be safe and return home in that same safe condition,” Helling said.

Minnesota Reformer is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Minnesota Reformer maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor J. Patrick Coolican for questions: info@minnesotareformer.com.