Howie's column is powered by Lyric Kitchen · Bar

The most expensive thing in American health care isn’t a drug, a surgery or a new technology. It’s the wrong incentive.

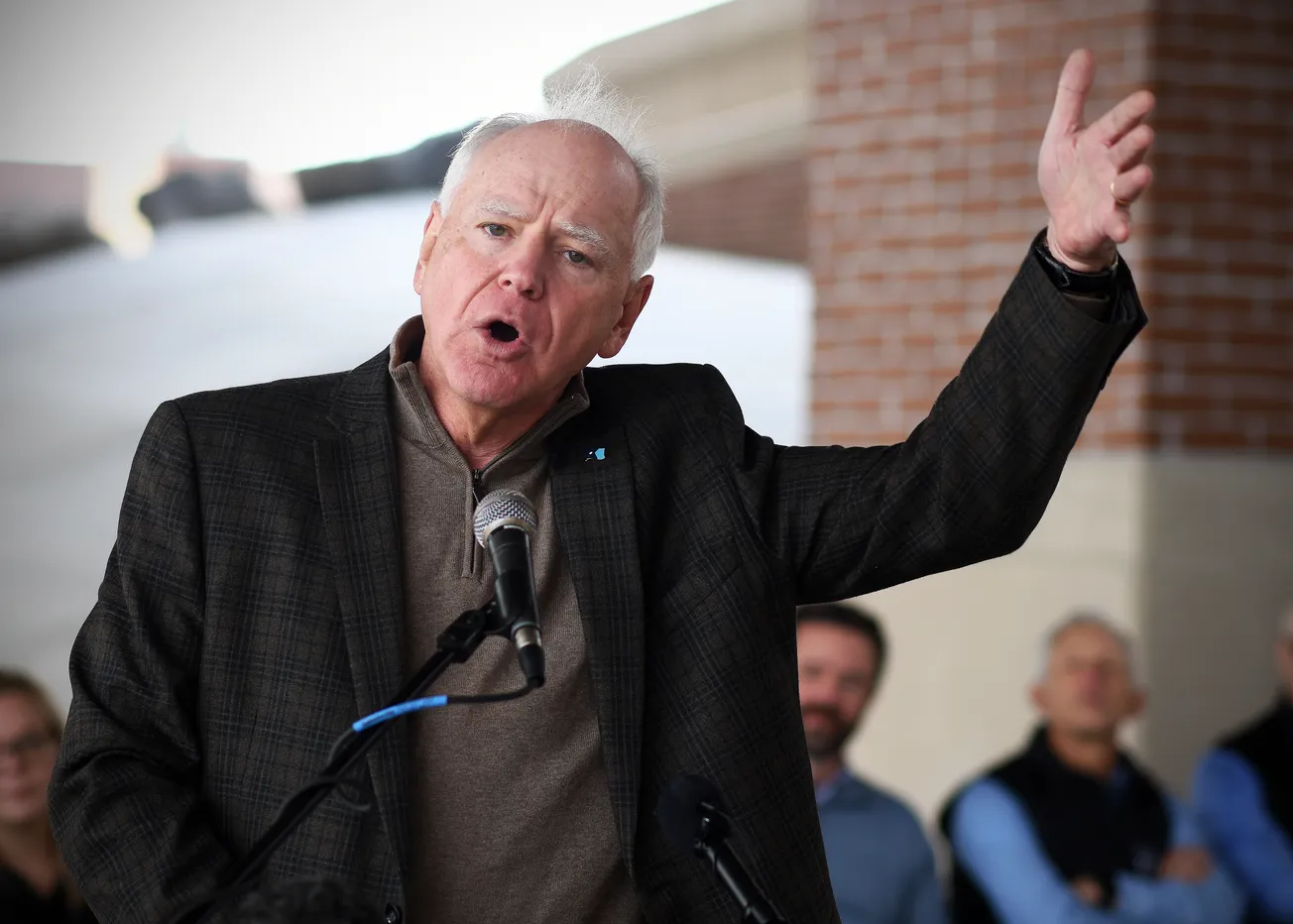

For more than a century, we’ve paid doctors by the slice — one procedure, one payment, one more line on a ledger. When Dr. David Herman, chief executive of Essentia Health, appeared before the United States Senate, he described that model plainly.

“Traditional fee-for-service pays for specific, itemized care delivered by clinicians,” he said. “It rewards volume rather than quality … and discourages practice transformation and innovation.”

In Duluth, he and his team stopped theorizing about reform and simply did it. Nearly forty percent of Essentia’s revenue now flows through value-based contracts — agreements that pay for outcomes, not output.

If diabetic control improves or unnecessary ER visits fall, Essentia shares in the savings. If not, they take the hit. The math is blunt, but the mission is moral: keep people healthy and make it pay to care.

It’s old-fashioned in spirit, futuristic in design.

“Value-based health care emphasizes prevention and wellness, in addition to treatment,” Herman said. “It focuses on connecting patients with the appropriate care at the right time and providing access to integrated care through the entire patient journey.”

Inside the system, that means teams instead of silos — nurses, pharmacists and community-care associates meeting weekly to review high-risk patients. When a heart-failure patient’s weight spikes, someone calls before the crisis. When a new mom misses an appointment, a navigator finds out why. It’s medicine re-rooted in relationship.

The numbers tell the story. From 2018 to 2021 Essentia cut more than $102 million from the total cost of care while meeting 98 percent of Medicare quality targets and still posting a 4 percent savings rate for taxpayers.

“We have demonstrated that investing in value-based care can be successful,” Herman said. “It is a pathway to the future of providing care in rural areas.”

Nationwide, health spending hit $4.3 trillion in 2021. Herman told senators that no budget line item could repair that reality; only a mindset shift could. If Washington is looking for a map out of its own fiscal ICU, it might start at the corner of Superior Street and Fourth Avenue East in Duluth.

In northern Minnesota, “rural” means long drives, aging populations and stubborn broadband gaps. Herman says that when you live in a rural area, you’ve made a decision — but you may not have realized what it costs.

“When you think about the economic costs … about having your son or your daughter take a day off work to drive you from Ely to Duluth for a 20-minute visit and then drive back, that could be better served by a community paramedic.”

He broke the cure down to three principles: “Know who your patients are. Know what they need. Get it to them before they really need it. That promotes health, wellness and well-being — and it decreases the cost of care.”

It’s a philosophy now reverberating across Minnesota’s health landscape. The state’s Integrated Health Partnerships (IHP) program already covers more than a third of Medicaid enrollees under total-cost-of-care contracts, generating more than $400 million in savings since 2013.

Its Health Care Homes model — team-based primary care built on coordination and prevention — forms the plumbing that lets clinics thrive under value-based payment. The Minnesota Department of Health’s Rural Health Transformation initiative is channeling new federal funding to expand those models statewide, mirroring Herman’s playbook.

Networks are rising to meet the moment. The Headwaters High-Value Network, a coalition of seventeen independent hospitals and clinics from Fergus Falls to Dawson, is pooling risk and contracting together to make value-based care viable in low-volume markets.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota has moved beyond talk, entering a full-risk partnership with Homeward Health to serve twenty-four rural counties — tying every payment to improved outcomes for Medicare Advantage members. These efforts echo Herman’s mantra that the incentive must finally match the mission.

Even as the movement gains ground, the system still tilts toward the old logic of throughput and billing. Congress is trying to catch up. The Value in Health Care Act would restore the 5 percent incentive for Advanced Alternative Payment Models and fix the thresholds that now exclude smaller rural providers.

Meanwhile, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has launched a $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Program to help states redesign their payment systems for the next decade. Minnesota is well-positioned to draw on that fund; its infrastructure is already half-built.

But Washington’s clock is ticking. The Medicare telehealth flexibilities that made rural access possible during the pandemic expired this month, snapping back to narrow “originating site” rules. Without new legislation, rural patients who relied on video visits with city specialists may lose them again. The transformation Herman envisions depends on those digital lifelines staying open.

He warned senators that the nation can’t afford to let reform stall: “A cost of that care will now need to be shifted to other people paying the cost of their care … All of that money that used to come from Medicaid will be placed upon their bills.” Translation: when the incentives stay wrong, everyone pays — especially those least able.

From Ely to Bemidji, Cloquet to Fargo, the evidence is mounting that Minnesota’s rural systems are ahead of the federal curve. Essentia’s own record — forty percent of revenue under value-based contracts, $102 million in savings, 98 percent of quality targets met — is now national proof.

The Headwaters Network and IHP program show how even the smallest hospitals can join the movement. The Blue Cross – Homeward partnership demonstrates that insurers can embrace it too.

Herman’s model is becoming the backbone of a new rural compact: align incentives with outcomes, build community-based teams, extend broadband and telehealth, and pay doctors for keeping people well.

“It supports our clinicians and care teams,” he said. “A team-based approach allows clinicians to spend valuable time with their patients and to contribute their own innovations.”

When payment rewards health instead of volume, a doctor can linger an extra ten minutes and listen — to a farmer’s stress, a mother’s fear, a veteran’s fatigue—without feeling punished by the clock.

The wrong incentive, Herman reminds anyone who will listen, remains the costliest thing of all. But the right one — the one now being tested in Duluth, in small-town hospitals, and in state agencies quietly rebuilding the machinery of care — might just rewrite the story of rural America. If Congress follows through, if payers hold their nerve, if more states mirror Minnesota’s lead, the transformation he began could finally stick.

For once, a health-care revolution isn’t coming from Silicon Valley or Washington, but from the north shore of Lake Superior. And if it succeeds, the light in the pharmacy window — the one Herman says tells you whether a town is still alive — might stay on a little longer.

Howie Hanson has reported on health care, politics and regional economics in Minnesota for more than five decades. His work focuses on the intersection of policy and people — where hospital corridors, legislative chambers, and small-town streets all tell the same story.