Howie's column is powered by Lyric Kitchen · Bar

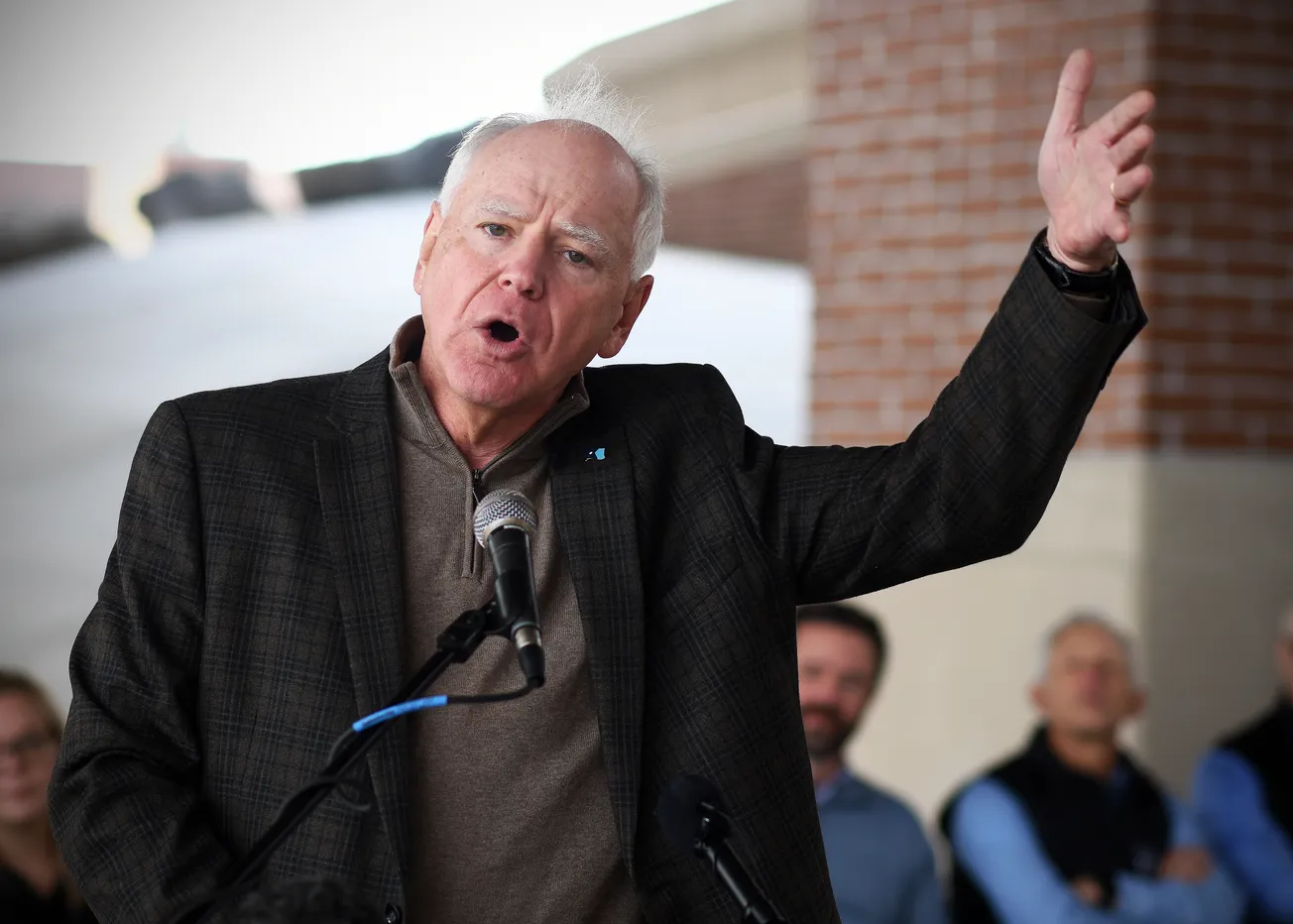

Ask Dr. David Herman what really drives health outcomes in the Northland, and he won’t start with stethoscopes. He’ll start with groceries, rent, and gas.

“Health is created through social, economic, and environmental factors in addition to health care access and individual behaviors,” he told U.S. senators.

Essentia Health now screens every patient for basic needs — food, housing, transportation — and the numbers are jarring. Of 144,000 people surveyed, more than 20,000 reported at least one unmet need. In some high-poverty clinics, more than half of all patients lacked something as simple as a reliable ride.

Herman sees these findings not as charity cases but as clinical data.

“If you don’t eat well or can’t afford heat, your blood pressure won’t care what your insurance card says,” he said.

Essentia built a digital platform called Resourceful, connecting providers directly to food shelves, housing agencies, and transit vouchers. A doctor can now make a referral with the same keystroke used to order an MRI. Within two years, more than 10,000 patients were referred; 30 percent received documented help. That is public health without the paperwork.

The disparities cut along racial lines. Herman’s team found that 22 percent of American Indian and 17 percent of Black patients reported food insecurity, compared with 7 percent of white patients. He called it “an inequity we can measure — and therefore, we can change.”

This is where value-based care meets justice. When hospitals are paid to keep people healthy, they suddenly have reason to care whether a family has groceries. And when clinicians are graded on blood-sugar control, they have reason to care if the nearest store sells anything besides beer and beef jerky.

The project isn’t glamorous. There are no ribbon-cuttings for bus tokens. But it’s the kind of quiet reform that saves lives before the sirens start.

“Connecting to other social services is a critical part of population-health improvement,” Herman told the Senate. “Access to healthy food, transportation, and housing must be seen as part of health care.”

In the Northland, where a frozen pipe can end a senior’s winter, that statement lands less like policy and more like truth.

As this series Minnesota’s Rural Health Reckoning continues next week, we pause to consider: what happens when you place food, heat, housing and transport at the center of a rural health system’s strategy? And what if the model is being led here, in this region, by Essentia?

Essentia’s screening of 144,000 patients and identification of over 20,000 with at least one unmet social need demonstrates a system willing to treat social issues like vitals.

Their population-health strategy explicitly includes screening for social determinants of health (SDOH) across all patients, and embedding referrals and partnerships with community resources.

In rural America generally, screening for food insecurity, transportation and housing is known to occur — yet fewer systems integrate referrals at scale. A recent national study found that in rural Iowa hospitals, although 94 percent identified food insecurity in needs assessments, only about 54 percent had implementation plans addressing it.

By contrast, Essentia is operating such implementation at meaningful scale.

This matters because social needs are not side issues. A family who cannot keep their utility bills paid or lacks reliable transportation to a pharmacy is automatically at higher risk. In places where the nearest grocery store is 30 miles away and winter arrives early, the stakes are amplified.

What makes a system lead? Several elements stand out in Essentia’s case:

. Screening is universal: The Community Health Needs Assessments and internal tracking show that Essentia has embedded social-need screening into primary care and hospital admissions. For example, their FY2024 data show food worry and food insecurity metrics tied to their screening tool.

. Platform integration: The Resourceful platform links clinical workflow with community-based resource directories. More than 4,500 programs in the directory; more than 8,000 searches in Duluth alone focused on food, housing and healthcare resources; and more than 1,000 referrals in the first year.

. Workforce and community health workers: Essentia expanded community health worker (CHW) programs to connect patients with housing, food and transit needs. In 2024 they screened 220,000 patients and 26,000 reported at least one need; CHWs support those patients.

. Data drives change: By measuring screening rates, unmet-need rates, tracking referrals and looking at disparities by race and geography, Essentia can move from anecdote to strategy.

In short: screening + referrals + data + community partnerships = operationalizing the social side of medicine.

In rural settings the challenges amplify:

. Distances are long, transportation options limited. If a patient cannot get to the clinic, follow-up fails.

. Weather, housing stock and heating costs are more volatile. A broken furnace becomes a health emergency.

. Grocery access may be poor; walkability is limited; food deserts are real.

. Social services may be far away, under-resourced or fragmented.

Essentia’s approach acknowledges that in rural Minnesota and neighboring states, these issues aren’t peripheral — they are the care pathway. By treating “no ride, no heat, no food” as a health-care variable, they shift what “care” means.

When the nearest store is 50 miles away, a physician worrying only about HbA1c misses the bigger picture. When a patient skips medications because heat bills drained the budget, cost-control fails.

Even with the leadership seen here, significant obstacles remain.

Firstly, funding and reimbursement for addressing social determinants lag. Hospitals can screen and refer — but paying for the non-clinical interventions (bus vouchers, emergency heating, food boxes) remains uneven. For rural systems on tight margins, scaling such programs is challenging.

Secondly, community-resource capacity is uneven. Screening identifies need; the question becomes: can the housing agency, food shelf or transit service absorb the referrals? Without that linkage, screening becomes merely data collection.

Thirdly, measurement and outcomes must follow. It’s not enough to refer; we must show that addressing those needs lowers hospitalizations, improves chronic-disease control, improves longevity. Essentia is advancing this, but rural systems across the nation remain early stage.

Fourthly, rural policy frameworks must evolve. While many states and the federal government are discussing social-determinants integration, legislation and regulation that embed social-care funding into health-system contracts are still nascent.

What makes this story more than local is that it offers a replicable model: a rural health system recognizing that social care is health care — and acting accordingly. It shows that in a geography where constraints multiply, you cannot treat social needs as optional.

For other rural systems and for national policymakers, the key implications are:

. Start with screening for basic needs in every clinical interaction.

. Build tech-enabled referral systems embedded in the workflow (not as add-ons).

. Link to community partners and deploy workforce (CHWs) who can navigate the non-medical aspects.

. Track data by demographic and geography to highlight inequities and measure progress.

. Advocate for payment and policy models that reward health outcomes, not just service volume.

Howie Hanson has reported on health care, politics and regional economics in Minnesota for more than five decades. His work focuses on the intersection of policy and people — where hospital corridors, legislative chambers, and small-town streets all tell the same story.

Editor's Note: Minnesota’s Rural Health Reckoning is an editorial journey through the state of rural health care in Minnesota, featuring one column each day for 13 days.

It looks beyond the headlines and into the exam rooms, the nurse stations, the broadband gaps and backroads where small-town medicine is quietly being rebuilt. Each installment examines one piece of the transformation — from how hospitals survive when the math stops working to how doctors, nurses, and patients are rewriting the rules of care from the inside out.

The story begins in Duluth, where Essentia Health has spent the past decade turning words like “value-based care” into something that actually lives in rural communities. But this isn’t just a health system’s story — it’s ours. What happens to medicine in Minnesota’s small towns will define who we are, how we age, and whether we can still look after one another when it matters most.

No organization sponsored this reporting. No PR firm pitched it. It’s one veteran columnist watching Minnesota’s health-care revolution unfold from the inside out — and trying to make sense of what it means for all of us.